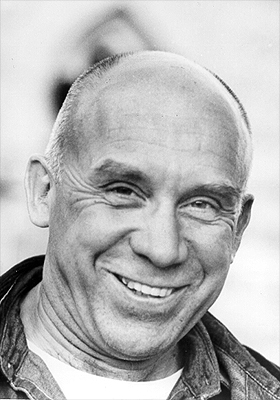

There are all sorts of questions we may reasonably ask about the nature of our "self". Depending upon our initial presuppositions and starting premises and depending upon the level at which we are dealing with the problem, we may get different answers. Since it is Sunday today, I naturally turn my attention on what spiritual people generally refer to as my "soul" and which a-religious people would refer to simply as my "self". I picked up a book which I bought a few days ago at the recent Hong Kong Book Fair. It's called "The New Man" (1961) by Thomas Merton (1915-1968), one of my favourite spiritual writers. Ever since having first laid my eyes upon the Chinese translation of his book "Inner Experience", I have been looking for other books by this contemplative monk who nevertheless had been most actively involved in the "secular" questions of this world until his untimely death after an East-West monastic dialogue conference in Bangkok on Dec. 10, 1968, the 27th anniversary of his entry into the Trappist (Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance ) Abbey of Gethsemani. But I only managed to buy just one other book by him, called "No Man is an Island" . It seems that his books are not that popular in Hong Kong. .

According to the official website of the Thomas Merton Center of the Bellarmine University, Merton is "arguably the most influential American Catholic author of the

twentieth century. His autobiography, The Seven Storey Mountain, has sold over

one million copies and has been translated into over fifteen languages. He wrote

over sixty other books and hundreds of poems and articles on topics ranging from

monastic spirituality to civil rights, nonviolence, and the nuclear arms race." He was the son of two artists and was born in Prades, France and after "a rambunctious youth and adolescence", he converted to Catholicism whilst at Columbia University and then in 1941 entered the Abbey of Gethsemani. He stayed there for 27 years and whilst there, considering that race and peace as the most urgent problem of our times, he became the "the conscience of the

peace movement of the 1960's" but for this "social activism

Merton endured severe criticism, from Catholics and non-Catholics alike, who

assailed his political writings as unbecoming of a monk". In his last years, "he became deeply interested in Asian religions,

particularly Zen Buddhism, and in promoting East-West dialogue...The Dalai Lama praised him as having a more profound understanding of Buddhism

than any other Christian he had known."

| |

In a chapter entitled "Spirit In Bondage", Merton sets out his views on the spiritual plight of the modern man. He goes really deep. In fact, all the way back to the original "sin" of Adam. According to him, Adam's principal sin was that he fell for an illusory "self": "the sin of Adam which robbed him and us of paradise was due to a false confidence, a confidence which deliberately willed to make the option and experiment of believing in a lie."

Merton saw no reason why Adam should be so foolish. "There was nothing in Adam's perfect peace that warranted this playing with unreality....There was no weakness, no passion in his flesh, that drove him to an irrational fulfillment in spite of his better judgment. All these things would only be the consequence of his preference for what 'was not'. Even the natural and healthy self-love by which Adam's nature rejoiced in its own full realization could gain nothing by adding unreality to the real. On the contrary, he could only become less himself by being other than what he already was." But why did he still do it? His answer is: pride: "For pride is a stubborn insistence on being what we are not and never intended to be. Pride is a deep, insatiable need for unreality, an exorbitant demand that others believe the lie we have made ourselves believe about ourselves. It infects at once man's person and the whole society he lives in."

Adam's pride had an effect: concupiscence: the convergence of all passions and all sense upon himself. I remember first coming cross this oddly sounding old fashioned word when I was still in Form 1. The "Brother" who was teaching us "Ethics" was not able to explain what exactly this word meant. I don't blame him. How do you expect a boy of twelve to understand such a profound concept. According to Merton, pride and selfishness then react upon one another in a vicious circle, "each one greatly enlarging the other's capacity to destroy our life." This pride led to "a form of supreme and absolute subjectivity. It sees all things from the viewpoint of a limited, individual self that is constituted as the center of the universe". Isn't this what we see everyday around us: people who would or could think of nothing and no one but themselves, people who think that the whole universe should revolve around their personal needs, their personal whims and desires and that everyone and everything else have only one purpose: to satisfy them when, where and how they wish. Listen to what our children are asking of us and their school and their "friends". Listen to what our politicians are asking for on behalf of their "constituents. and you'll get a pretty good idea of what I mean.

Merton understands why we are the way we are. He says, "now everybody knows that, subjectively, we see and feel as if we were at the center of things, since that is the way we are made." But pride adds something else on to this general and understandable mistake: "pride ...elevates this subjective feeling into metaphysical absolute. The self must be treated as if, not merely in feeling but in actual fact, the whole universe revolved around it." Concupiscence, enlisted in the service of pride, tells us, "If I am the center of the universe, then everything belongs to me. I can claim as my due, all the good things of the earth. I can rob and cheat and bully other people. I can help myself to anything I like, and no one can resist me. Yet at the same time, all must respect and love me as a benefactor, a sage, a leader, a king. They must let me bully them and take away all that they have and on top of it they must bow down, kiss my feet and treat me as god." This is a most childish attitude.

In a way, we have never grown up. The root of all our problems both individually and collectively is that age has done nothing to alleviate this general tendency towards selfishness and self-centered-ness. We continue to behave like a baby all of our life and never learn humility. To Merton, "To grow up means, in fact, to become humble, to throw away the illusion that I am the center of the everything and that other people only exist to provide me with comfort and pleasure." We only got to look at the advertisement bombarding us daily from MTR posters, television, cabled or wireless, newspaper, magazines, huge LED screens erected outside commercial buildings to see if we are ever educated to think of others or whether they are not carefully calculated to feed and even encourage and stimulate our "subjective" but natural desires for making ourselves "appear" better than we are or positively misleading us in thinking or dreaming to be what we are not!

It is obvious that society doesn't seem to help us grow up. To Merton, "Unfortunately, pride is so deeply embedded in human society that instead of educating one another in humility and maturity, we bring each other up in selfishness and pride." We are merely doing window dressing: "The attitudes that ought to make us 'mature' too often only give us a kind of poise, a kind of veneer, that make our pride all the more suave and effective. For social life, in the end, is too often simply a convenient compromise by which your pride and mine are able to get along together without too much friction". That is why, he says, "it is a dangerous illusion to trust in society to make us 'balanced', 'realistic' and 'humble'. I think he speaks with deep insight when he says, "Very often, the humility demanded of us by our society is simply acquiescence in the pride of the collectivity and of those in power. Worse still, while we learn to be humble and virtuous as individuals, we allow ourselves to commit the worst crimes in the name of 'society'. " We are gentle in our private life in order to be murderers as a collective group. For murder, committed by an individual, is a great crime. But when it becomes war or revolution, it is represented as the summit of heroism and virtue". This is precisely what I have been telling my friends all along. As a society, we are all hypocrites: we apply double or even multiple standards. Why did America invade (or in their own terminology "liberate" ) only Iraq and not some other equally African or Asian dictatorships doing ruthless massacres of what they regard as their enemies? Why did America condone or turn a blind eye towards Israeli atrocities and injustices perpetrated against Palestinian civilians but make mountains out of mole hills of Palestinian atrocities against Israelis. I am not saying that the Palestinians are right. But two wrongs don't make one right. That is a simple reasoning which everybody can understand. They are both wrong, but each in their own way. The leaders of each group are equally guilty of crimes against humanity.

Merton points to another hypocritical subterfuge practised by the modern man. He says, "One would almost think that the great benefit modern man seeks in collective living is the avoidance of guilt by the simple expedient of having the state, the Party, or the class command us to do the evil that lies hidden in our heart. Thus we are no longer responsible for it, we imagine. Better still, we can satisfy all our worst instincts in the service of collective barbarism, and in the end, we will be praised for it. We will be heroes, chiefs of police, and maybe even dictators."

What to do?

(to be cont'd)